Prototyping

Learning by building and testing

By putting tangible things in front of people who’ve been affected by cybercrime or fraud, we are able to learn about what they need and adjust our prototypes to address more of those needs.

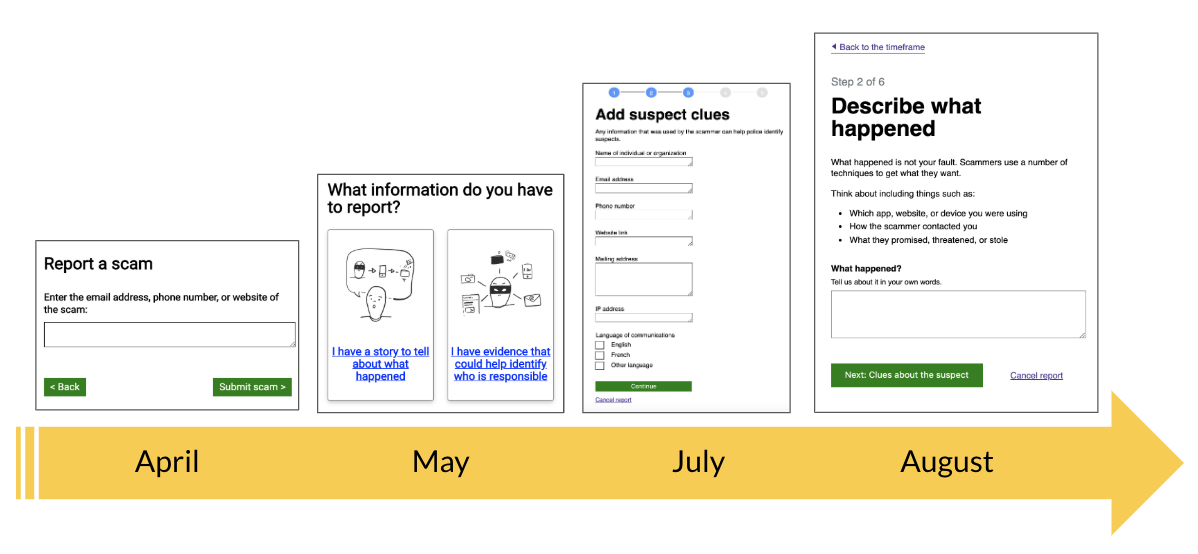

You can find an overview of the prototypes built, tested, and iterated on, so far, below:

- Concept 1: Reporting cybercrime with a single identifier (April 2019)

- Concept 2: Finding out where to report scams and online crimes (May 2019)

- Prototype 1: Reporting scams in a structured form (July 2019)

- Prototype 2: Reporting scams in an open form (August 2019)

Applying what we are learning to prototypes

Early on, we started building low-fidelity concepts as a quick way to test different directions. We put these in front of seniors, library-goers, and newcomers to Canada. Here are some of the insights we learned:

- Make the purpose and value of the service clear and have a strong call to action:

* Be explicit about which government or law enforcement entity will receive the report

* Reassure victims that this is not a scam

* Make the service accessible where people already report cybercrime and seek help

- Use language that resonnates with victims:

* Precise, direct, instructional, plain language

* Clearly define terms: "cybercrime", "evidence", etc.

* "Scams" rather than "cybercrimes"

* "Reporting" rather than "sharing"

As we learn more about what victims and police need, we can start to address more of those needs in the prototypes we’re building.

Simply asking for data is not enough

There are many barriers that affect victims’ ability to provide information especially without face-to-face interactions with someone who can empathize, provide context, and help a victim orient themselves in their situation. We have found that many of the things victims struggle with, police are burdened by as well.

Victims cannot provide data all at once, or without structure

Because they’re upset or confused victims find reporting can get overwhelming very quickly. Police tend to see a lot of incomplete reports, or lack of detail in reports because victims are too overwhelmed to answer all their questions.

“Some people will only answer 1 of 6 questions. It’s a lot for them to process.” — Frontline staff

We addressed this in the prototype by dividing the current iteration into short sections that are easily digestible.

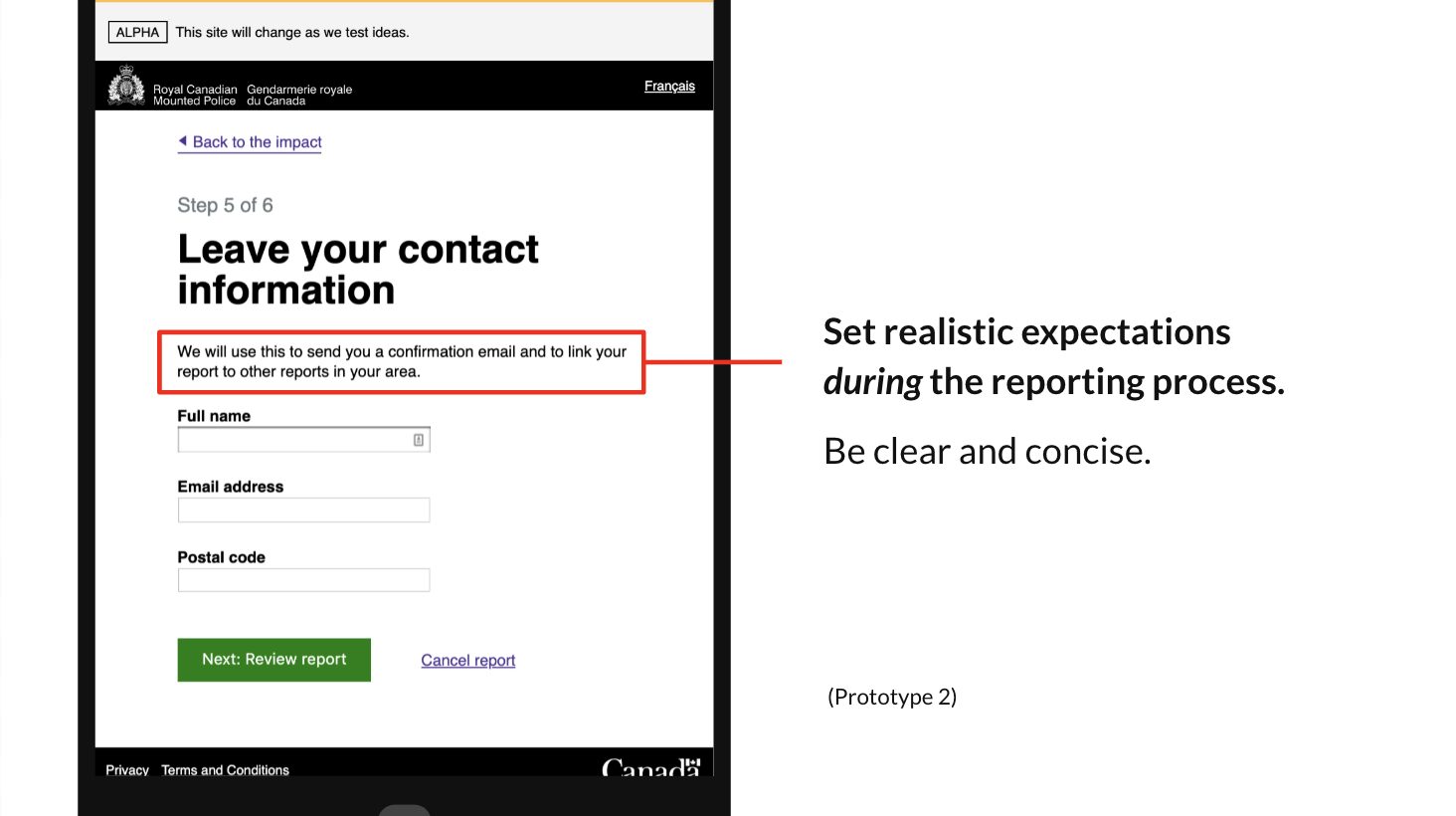

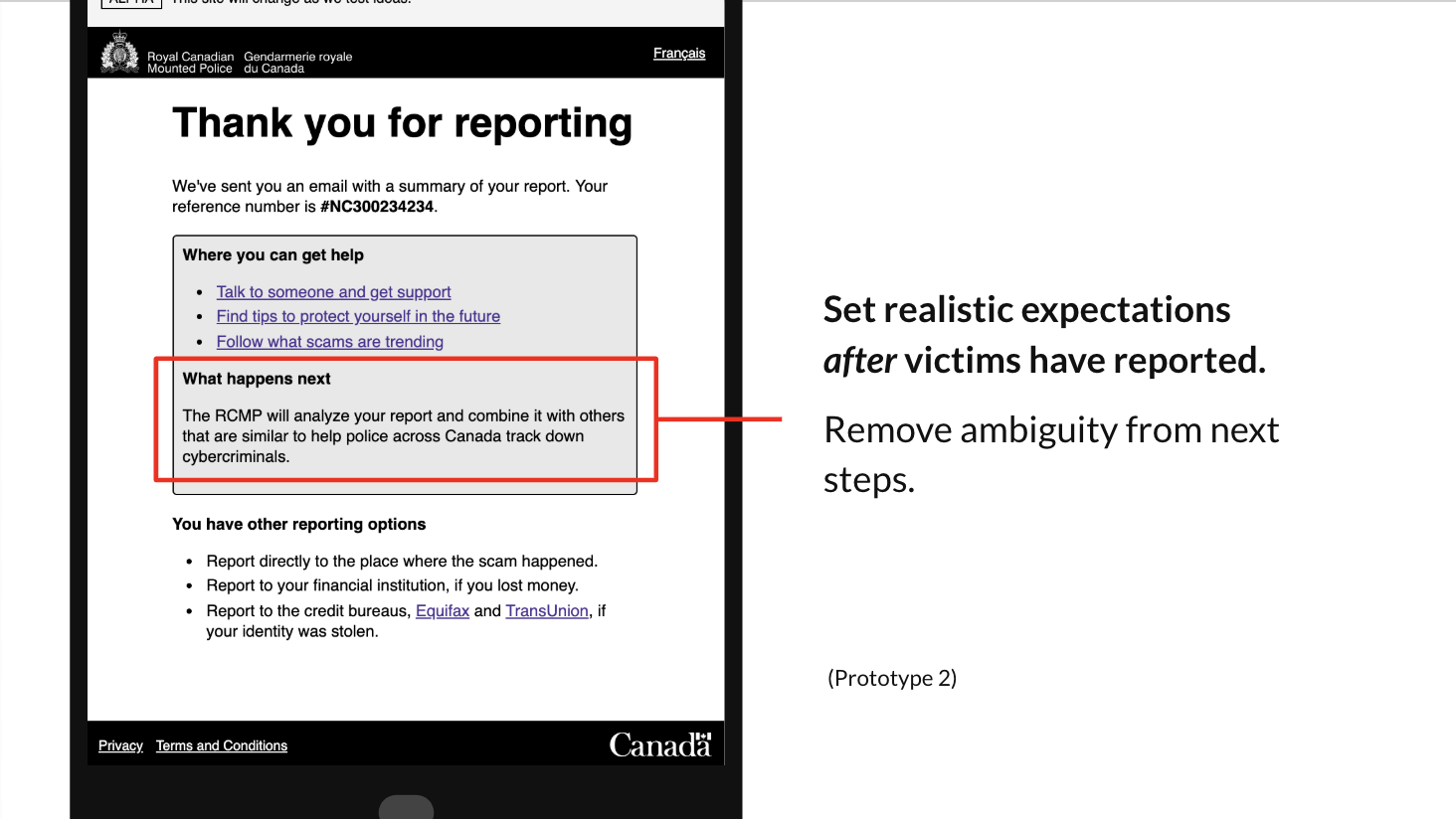

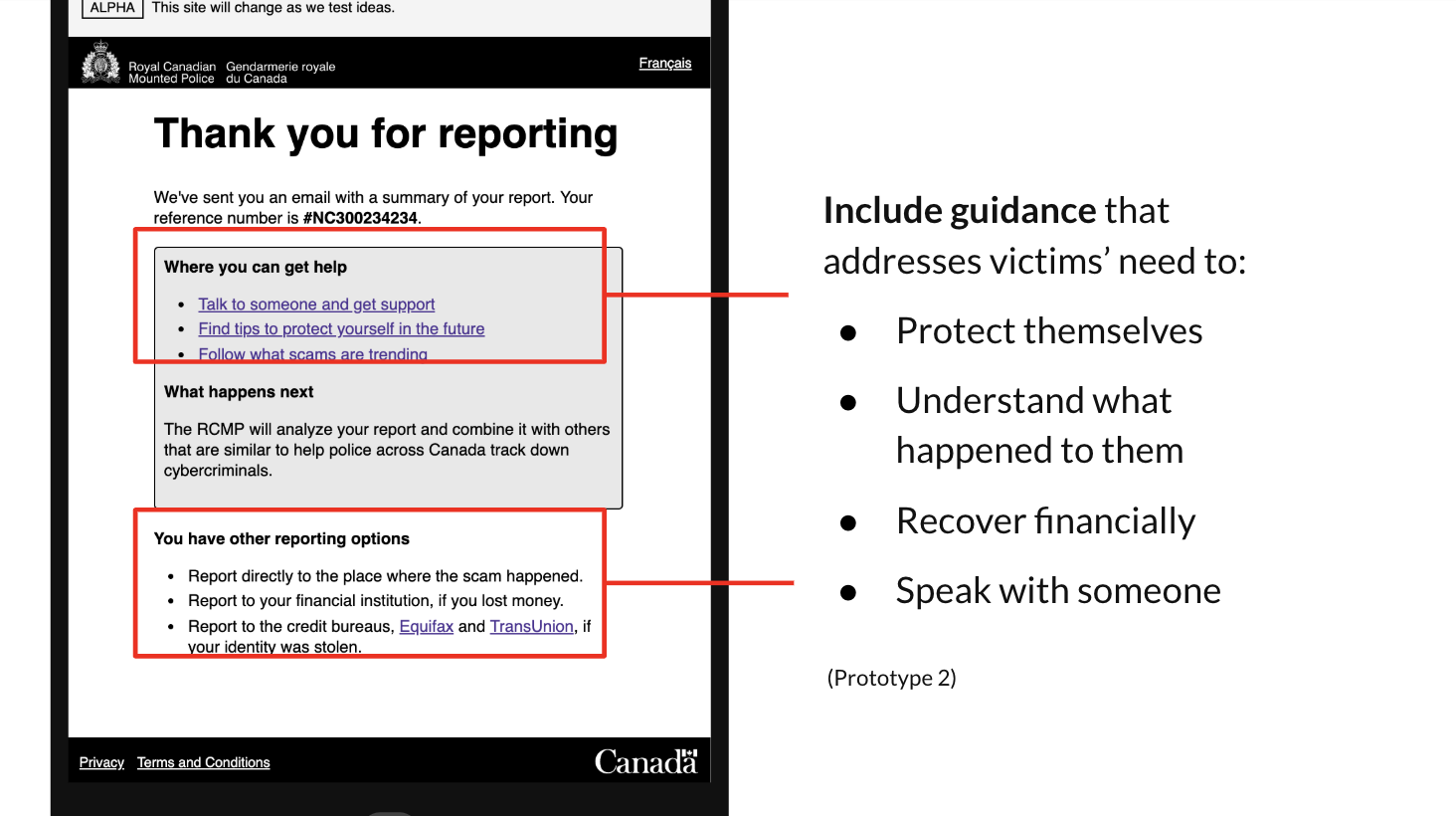

Victims feel let down and stop reporting when what happens next is not what they expect

Because this is a new experience for victims, they expect a follow-up phone call, interview, or some kind of written confirmation that the report was received. When next steps are not clear, victims can get anxious and call or visit the police in person to ask for updates.

“Victims visit the next day to ask for case updates or send emails to see if we received [their report]” — Frontline staff

In many cases, victims lose faith and stop reporting altogether because the process is not clear to them. They feel let down, when in reality they were not clearly informed at the source. In response to this, we are trying to use simple, clear language to let people know why reports are being collected and what to expect after reporting.

We are also trying to be clear on the final page about the goal of reporting: to stop cybercriminals. This sheds some light on where the report will go next and can help mitigate confusion about the next steps to prevent unnecessary follow-up with local police.

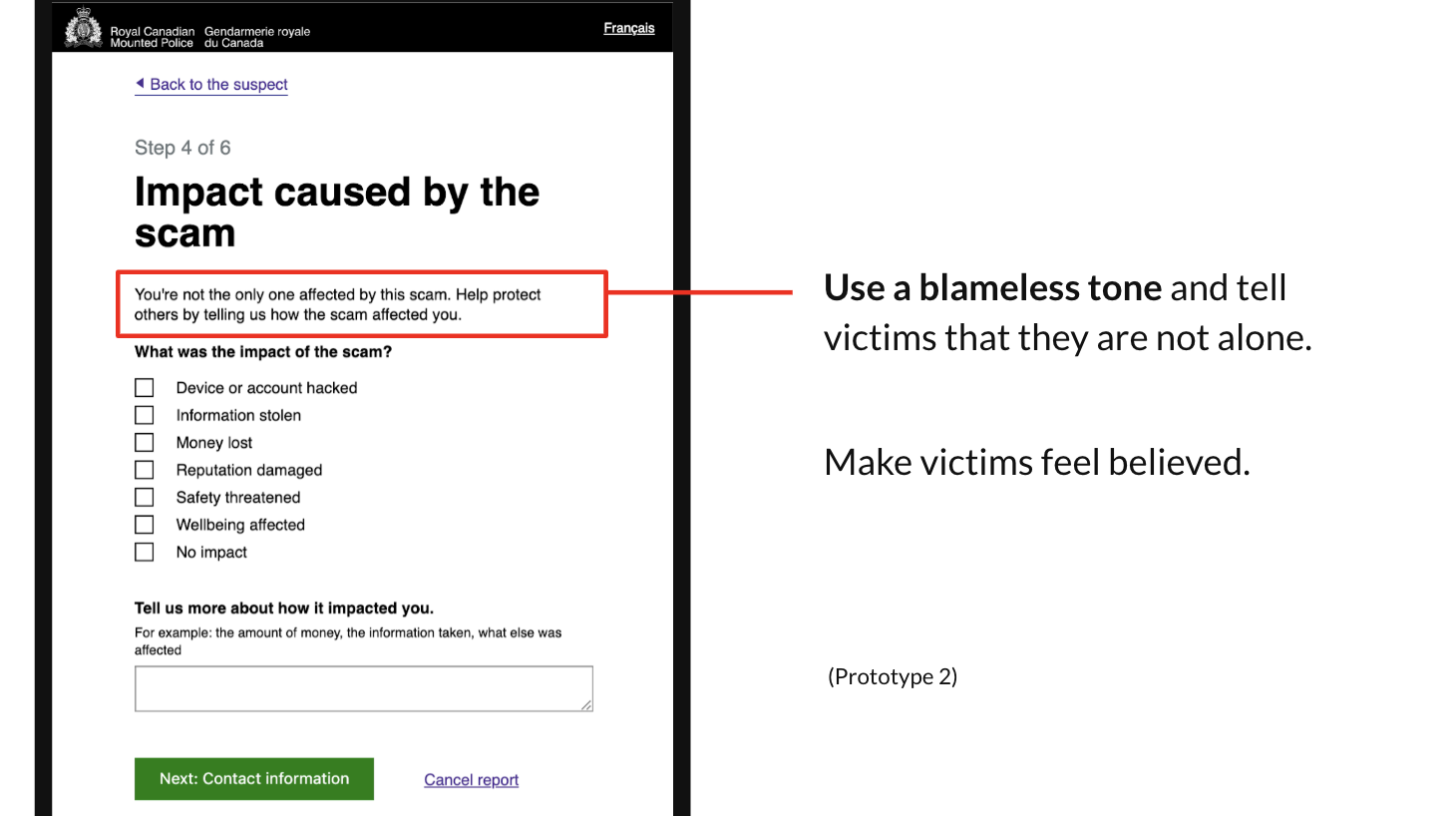

Victims avoid reporting because they’re ashamed and feel at fault

Because of shame, guilt, and embarrassment, victims avoid telling friends, family and police about what happened. They might think what happened is their fault, especially if they’re not tech-savvy. Police often put in extra time to reassure victims of cybercrime that it is not their fault. When victims feel comfortable enough to reach out and report, police are able to help them better understand what happened to them.

“When [victims] felt safe, and felt that it wasn’t their fault, they opened up more and provided more details” _ — Officer taking reports over the phone_

We’re trying to a blameless tone to acknowledge that people are in a difficult situation, that we’re there to listen, and that they’re not alone. It’s something that frontline staff and call takers do on a daily basis.

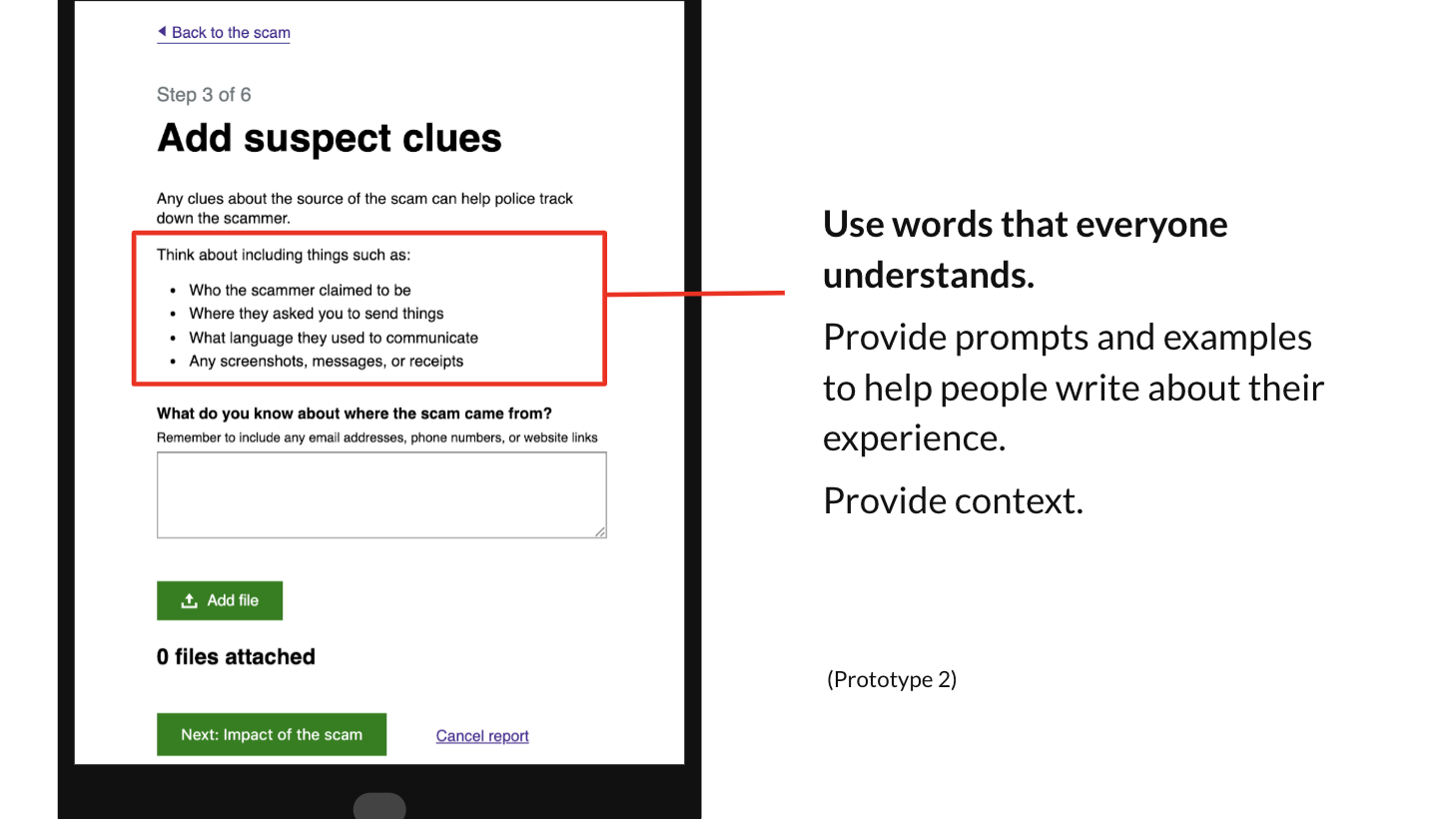

Victims use different language than law enforcement

The public does not have the same definitions for words that people in law enforcement do. Police reword required data fields so that victims understand them. Words like “evidence”, “suspect”, “fraud”, “cybercrime” have different definitions and police often give guidance to people and explain what these terms mean.

Instead of relying on those words alone, we want to add context and provide examples and guidance. This helps to reduce the mental work that people have to do to fill out the form.

Victims need to protect themselves from ongoing or future attacks

We are also learning that one of the biggest problems for victims and for police is the lack of preventative guidance and education around protecting yourself. When people report to the police they expect and hope that the police can help them. When police take calls, or help people in person, they try not to leave them hanging.

“I’m saying the same sentence day after day to these poor folks… there needs to be more preventative, proactive help. We get a lot of ‘I don’t know how I fell for this’, after the fact” — Officer taking reports over the phone

Victims are in a state of distress and confusion. They need clear next steps related to getting immediate help and protecting themselves in the future built into the service. When that help is found, they feel safer and more satisfied.

Putting prototypes in front of many users

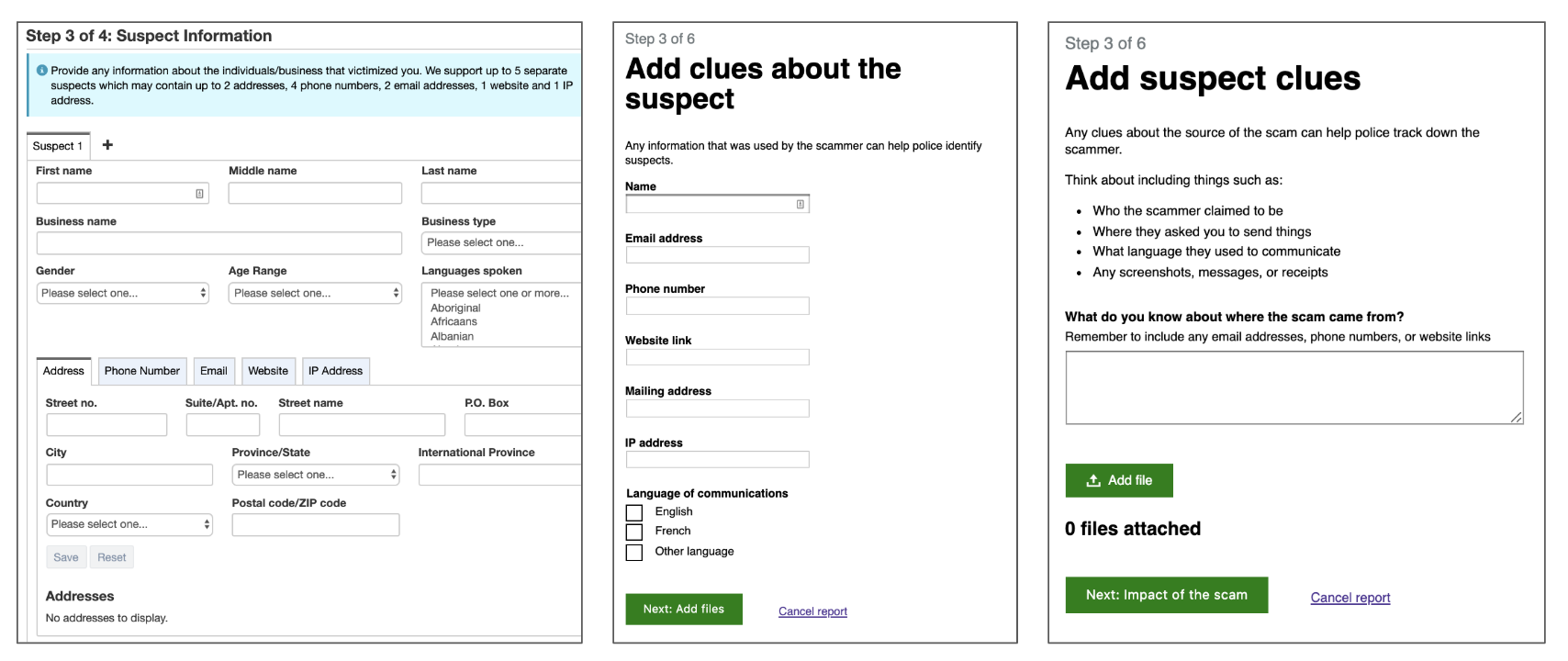

We are continuing to take what we learned from victims and police and applying it to prototypes through incremental, but informed changes. To test whether we’re meeting the needs of victims and police in the latest reporting form Prototype 2, we examined how this current iteration compared to other versions including the baseline fraud reporting system and an earlier iteration Prototype 1.

Prototype 1 features:

- Reduced content based on the baseline fraud reporting form

- Structured input fields re-designed to lower cognitive load

- Simplified layout, content, and interactions

- More accessible language

Prototype 2 features:

- Open fields that provide flexibility

- Language that provides emotional reassurance

- Examples and prompts that provide guidance

- Clarity on purpose, next steps, and other options

Comparing prototypes in a large-scale test

The purpose of this large-scale test was to know how the current iteration compared in terms of:

- Quality of users’ experience reporting a cybercrime

- Users’ trust and confidence in the form

- The quality and quantity of reports submitted

What we learned

We found that participants were more likely to complete and submit a report when using Prototypes 1 and 2. People rated these prototypes as more usable and preferred to use the current iteration prototype (Prototype 2). Prototype 2 maintains quality with improved usability and loyalty, while increasing the quantity of reports submitted.

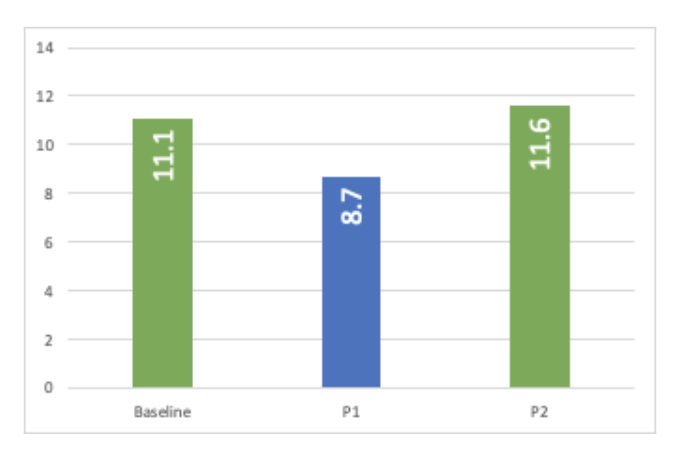

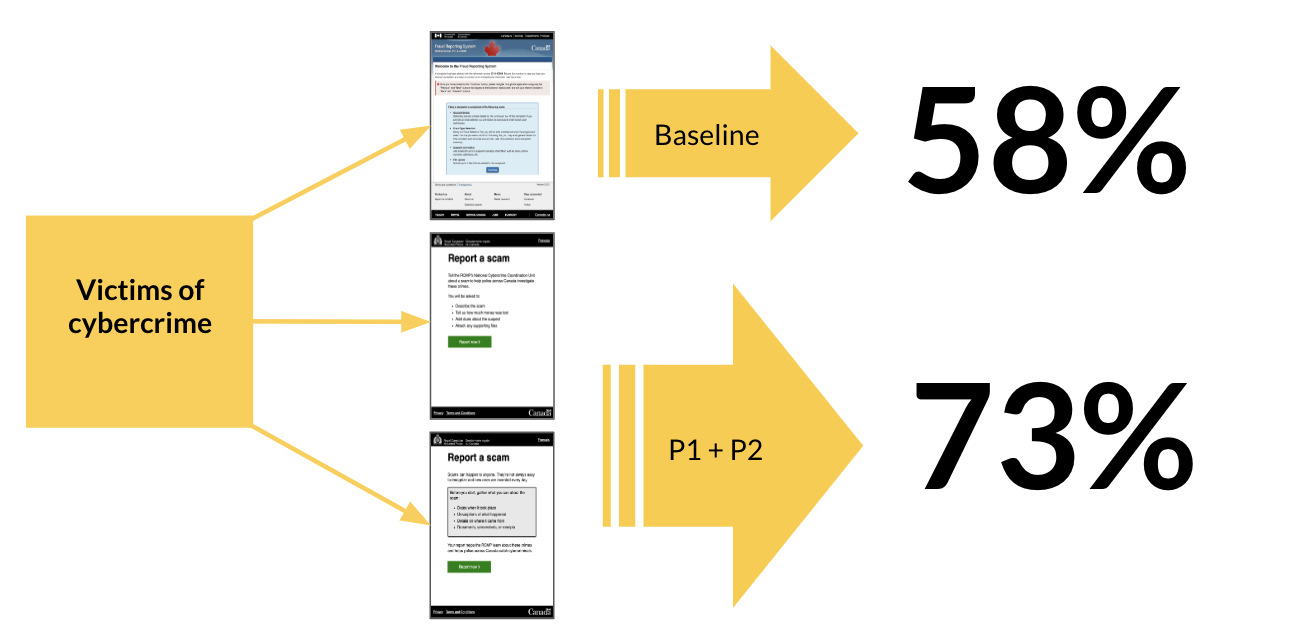

Quantity of reports submitted

People using Prototype 1 and Prototype 2 were more likely to complete and submit a report. Over 40% of people who used the baseline opted out of completing and submitting a report.

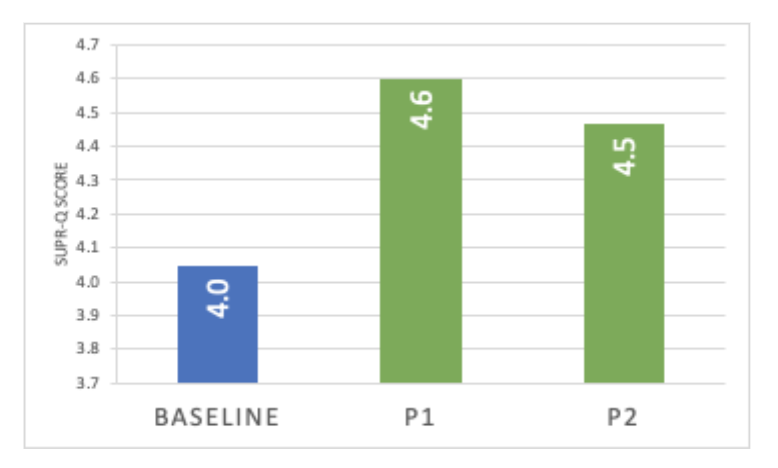

Experience using the service

People reported higher levels of usablity for both Prototype 1 and Prototype 2 compared to the baseline form.

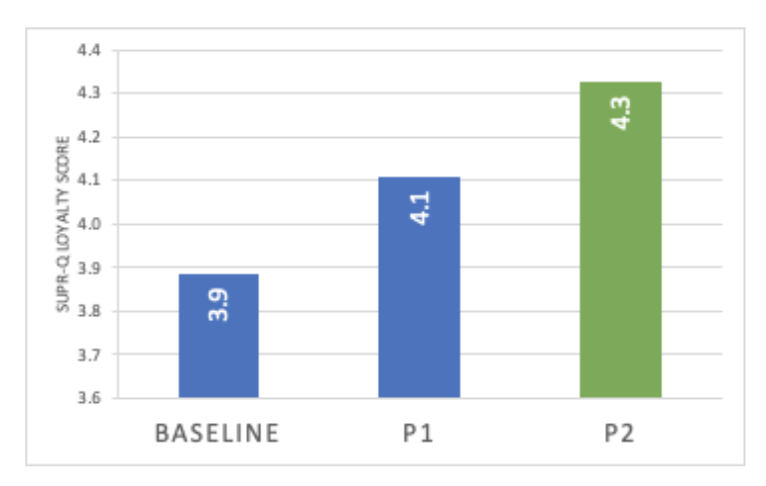

Experience and intention to use the site

People reported greater intentions to use the current iteration (Prototype 2) than either the baseline form or Prototype 1.

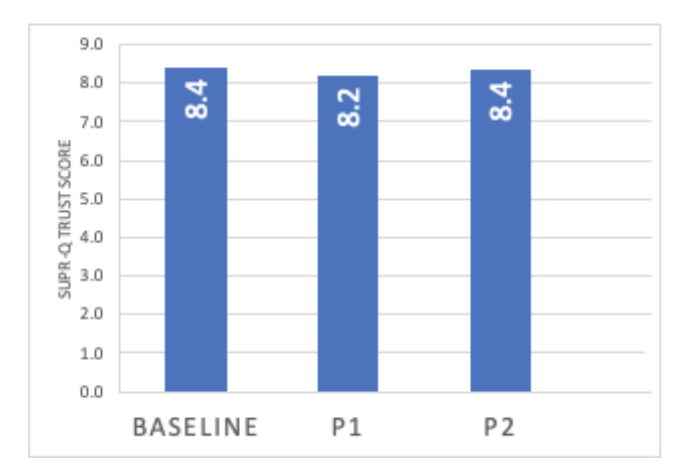

Trust and confidence

People reported equal ratings of trust and confidence in reporting for all three versions of the form. They are also equally likely to recommend each of them.

Report quality

Each report was rated by three RCMP staff members and averaged. Reports from the current iteration (Prototype 2) and the baseline rated as of the same quality.